M1-46 Michael Nyman

I’m getting near the end of this blog, so I’d like to mention what a pleasure it is to have the time and space to expand on the miniature sleeve notes I was able to provide on the original album cover. An LP cover is 12” square, so that’s 12 x 12 = 144 square inches. Divided by 51 tracks, that equals a hair over 2.8 square inches per track. Not a lot of space in which to include track title, artist name, and a descriptive blurb. So, if I may, and for the first time, in the spirit of Michael Nyman’s systems music I’ll systematically go through Michael’s 1980 mini-blurb and build on each line. As Michael once said: “I’m not a great inventor from scratch. What I do is to use, steal, acquire, reproduce or re-cycle music from other musicians.” Here goes…

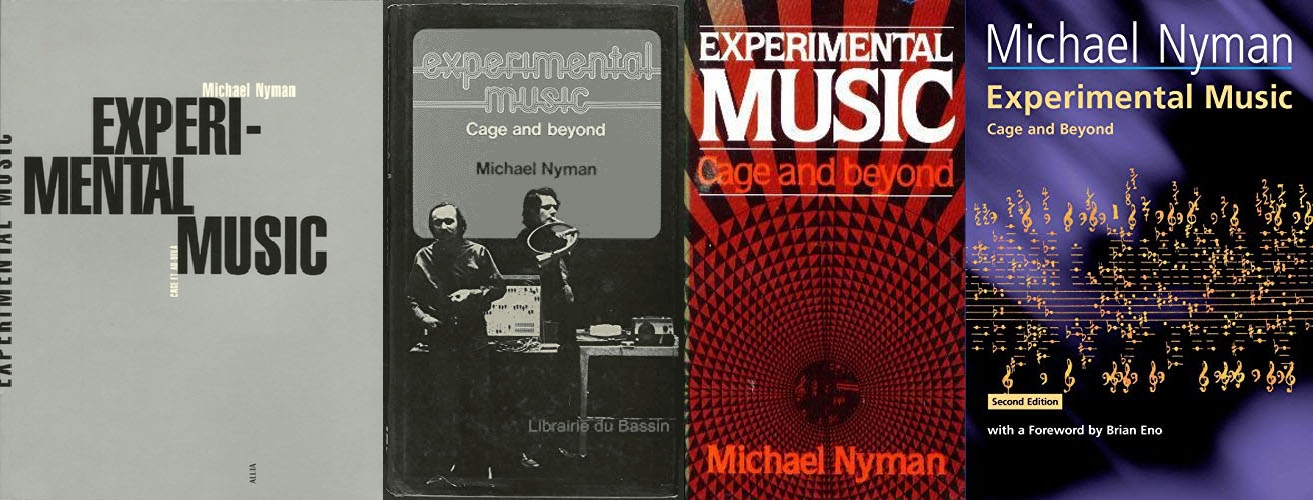

The author of “Experimental Music – Cage and Beyond” (Studio Vista 1974)

Almost 50 years ago there was nowhere near as wide a choice of books on contemporary music as there are now, especially the experimental, minimal and modern music that started in the 60s. Michael’s book filled a distinct gap in the field and thus became highly influential. It covered areas and and figures such as indeterminacy, electronics, Fluxus, Feldman, Cage, Ichiyanagi, Scratch Orchestra, and in the final chapter, determinacy, new tonality, and minimal music. He is credited for being the first writer to use the term “minimal” in music, although it had been applied to visual art since the mid-60s. The decade prior to the book’s publication marked a new departure from what avant-garde music had become (bafflingly complex and elitist). Influenced by the global impact of rock music, many composers were turning towards more sensual music, using simpler means combined with fresh, new, invigorating ideas that could communicate with a wider audience. It was almost as if Stockhausen had acquired a sudden passion for Louie Louie. Michael’s book was perfectly timed and written from the eye of this balmy but revolutionary cultural hurricane. 46 years on, it still makes a great read – even more so with the added preface by Brian Eno.

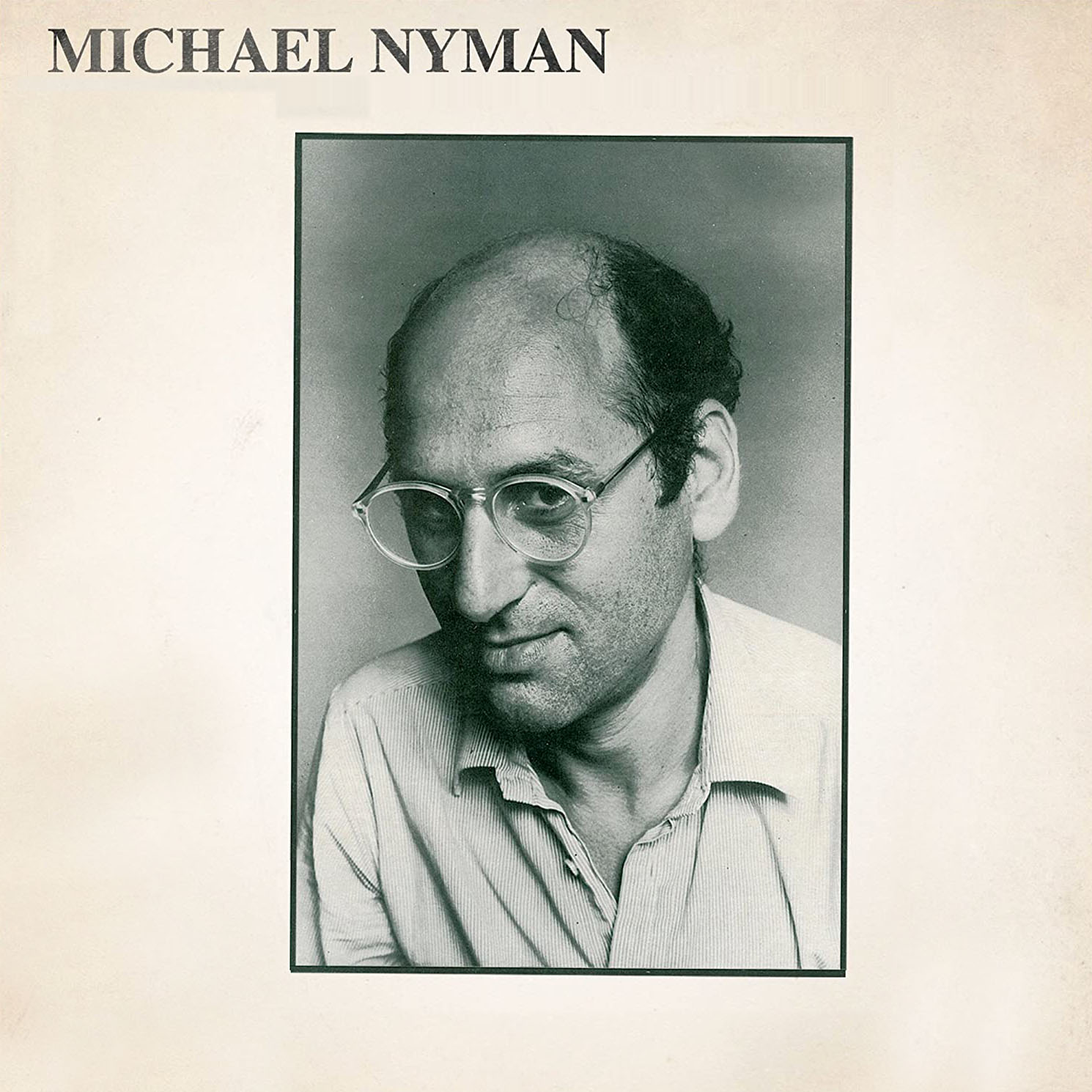

Mike formed his own band in ‘77

Actually the Michael Nyman Band was formed in 1976 to provide music for a performance of “Il Campiello,” a comedy by the 18th century Venetian Carlo Goldoni. It would seem they were a kind of street band, but without the use of a P.A., because he chose the more raucous instruments such as rebecs, saxophones, and shawms. The band enjoyed the experience and decided to continue, so Michael started to compose more for them, and fairly soon they evolved into a fully amplified line-up of string quartet, double bass, clarinet, three saxophones, horn, trumpet, bass trombone, bass guitar, and piano. Concerts, then, had some of the quality of the loudness of a rock band rather than a genteel salon orchestra. Pounding rhythms were a feature, even without drums or percussion. His miniature, then, is fairly typical of his work at that time. That said, quieter moments of great beauty such as this were also to be had.

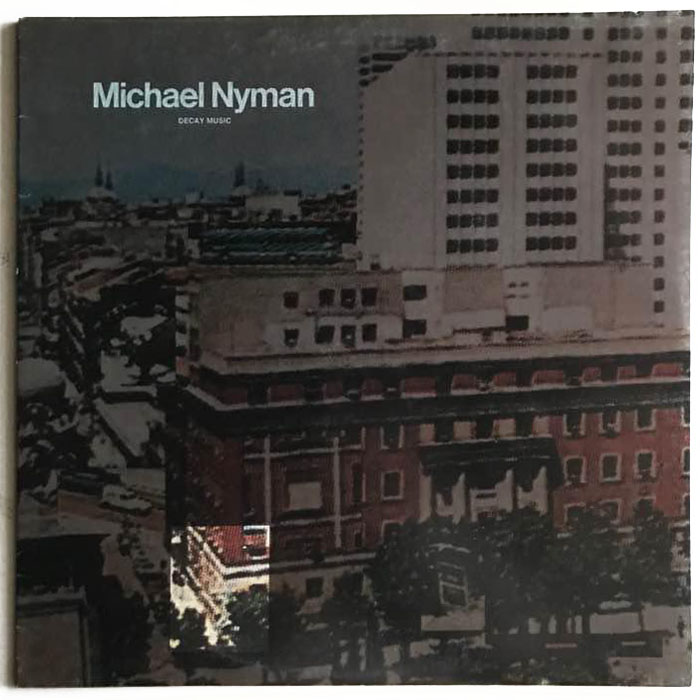

& also made a systems music LP, Decay Music (Obscure Records)

Also from 1976, this was Michael’s first album, and the sixth of ten albums released on Brian Eno’s Obscure Records label between 1975 and 1978. The label was distributed by Island Records, which was mainly a rock/reggae label, with acts such as Eno’s Roxy Music, Bob Marley, and the first version of my combo Mott the Hoople.

Numbers certainly played a big part in Michael Nyman’s early music. There’s a numeric simplicity and repetitiveness in it, but less obviously “minimal” than say, Glass or Reich. Even his birthdate is numerically sequential: 23/3/44. The first side of Decay Music was piano music composed to accompany a film called “1-100” by Peter Greenaway which consisted simply of the numbers one to a hundred, shot in various locations. Greenaway asked Michael to come up with a score that would be a musical parallel to the visuals. Michael was at that time analysing the famous Blue Danube Waltz by Strauss. To his surprise, he discovered that the first section of that piece contains exactly 100 bars, so he constructed his own piece by picking one chord from each bar and playing them in sequence but on various parts of the piano, with gradually increasing complexity. He also recorded it 4 times while only listening to the track he was playing, so that the out-of-sync mix of the 4 superimposed tracks created “unforeseen, accidental concurrences and staggered sonorities.”

He’s now working on a new version of ‘The Ride of the Valkyries’ for the Graz Festival (Austria Nov. ‘81)

This sounds like a fine idea, but on doing some serious googling 40 years on, I can find no mention of it anywhere. Please feel free to comment if you know anything about this projected performance. For now, I hope this rather miniature version of the Wagner classic will suffice.

& has created several scores for films by Peter Greenaway

Michael was Greenway’s preferred composer, at least from 1978 to 1991, and with both of them having a strong interest in the baroque era, it was a lasting and creative collaboration, resulting in some extraordinarily rich, colourful, highly acclaimed films such as The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), A Zed & Two Noughts (1985), Drowning by Numbers (1988), The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989) and Prospero’s Books (1991).

In 1994 Jane Campion’s film “The Piano” brought him to a much wider audience and massive success, with a score that was more emotional and warm than much of what he had composed till then. His career moved into a higher gear and he found himself scoring Hollywood movies such as Gattaca (1997), working with other leading directors such as Patrice Leconte and Michael Winterbottom, and garnering 11 major awards and 18 nominations – and a CBE – so far.

including ‘Vertical Features Remake’, ‘1-100’, & ‘A Walk Through H’

Vertical Features Remake (1978) is definitely on the experimental side of film-making. Quotes from IMDB user reviews include: The very essence of film / This is a complete masterpiece / made up documentary using random archive images of people and vertical objects like posts, poles, tree trunks etc in a domestic landscape / depicts four attempts by presumptuous analytical academics trying their own hands at attempting to reconstruct an artist’s vision / the amusingly foreboding piano key poundings that accompany and punctuate each scene are wildly different / leaving me in hysterics as the pianist is just assaulting the poor thing / The music reinforces the tediousness, and works as a spectacularly strange and minimal soundtrack, perfectly suiting the film. If you’re a film appreciator like myself, you have to watch this film. REALLY, IT’S THAT GOOD!

Of course there was someone who felt the need to whine: I must say I was more bored than entertained with this one here. Maybe Greenaway is best at 20 minutes max (the film lasts 43 minutes).

A Walk Through H: The Reincarnation of an Ornithologist (1979, another short – 41mins). Although a thumbnail description seems to indicate that it could be a dry, minimal-style film (“a multilevel tour of a museum, of the 92 drawings displayed therein, and of the experiences in collecting the drawings”) it has engendered some passionate reviews:

Easily one of the most thrilling and totally enjoyable films I’ve ever seen / as complete and expansive in scope as any epic out there / I honestly do not know of a more engaging film / the maps, the avian companions, the music, and the narrated story meld perfectly / like moving to another country and realizing one has learnt a new language without trying / the distinctive minimalist music of Michael Nyman. I felt the film was at its strongest latterly when this impressive soundtrack took centre stage at the expense of the narration.

This track utilises the titles music for the last 4 of the 92 biographies that make up Greenaway’s 1980 film ‘The Fall’

My mistake – the title is actually The Falls. One reviewer says of the previously-mentioned film: “This early work was greatly expanded in vision and changed from birth to death in the later ‘The Falls.’ But to plumb that film you must fight tedium.” Really? Let’s see some reviews of this 195-minute film, which was based on 92 BBC documentary-style shorts that record the lives of 92 unfortunate people, each a victim of a VUE (Violent Unexplained Event), and all with last names beginning with “Fall.”

“The musical score left me speechless, and after three hours of listening to it, I am sure it will be stuck in my head all day tomorrow at work. The way it progresses from one victim to the next is fascinating.”

“It [the film] is like minimalism, with a strict repetitive structure which builds towards a dramatic climax. Nyman’s score helps immeasurably in this development, beginning as isolated notes and chords, and finishing as an oratorio. The theme he wrote for the opening credits, “The Boulder Orchard,” is fabulous.”

Another passionate reviewer stated: “Greenaway’s collaborations with Michael Nyman (8 films) is every bit as strong as the collaboration between Reggio and Glass. I believe that both teams have produced some of the greatest films of the century.”

To conclude the commentary on the Greenaway/Nyman collaboration, here’s a quote from a review of Greenaway’s 1999 film “8 1/2 Women.” “Most damningly, this film suffers even more than ‘The Pillow Book’ or ‘The Baby of Macon’ from the absence of composer Michael Nyman. If the two men can’t patch things up, Greenaway needs to find another composer, and quickly, to fill the strange aural void left within his recent films.”

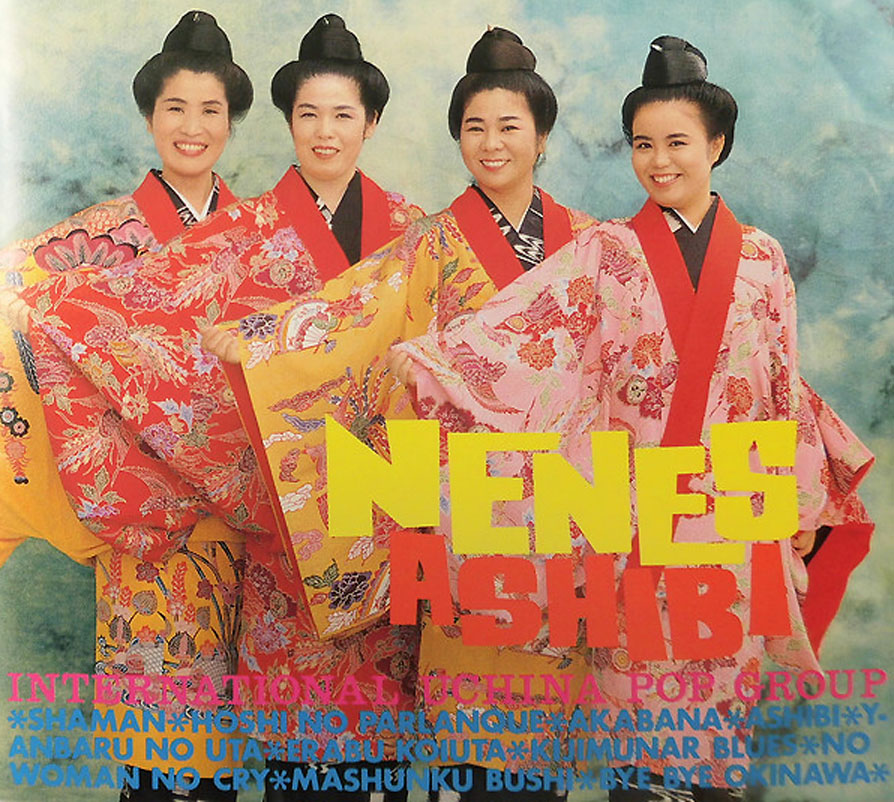

Somewhere along the line it seems that Michael felt the need to breathe different air. Japanese culture seemed to attract him, in particular Okinawan bands like the folk-rock band Nēnēs who he asked me about when he came here in 1993 to perform. He ended up visiting them in their “Shima Uta” (Island Song) bar in Naha, the capital of Okinawa, and produced a recording of them singing, among other songs, a moving version of Bob Marley’s “No Woman No Cry” at a fund-raising concert he organised in Okinawa to benefit victims of the massive 1995 earthquake in Kobe. He used this recording in his film “Earthquakes” – a 5-screen multimedia creation which opens with a scene of an old Japanese woman crying. It goes on to show scenes from earthquakes around the world. From 7:15 in this video, Michael talks about “Earthquakes” at length (the preceding part is also well worth watching even in Spanish, as it is a fine visual digest of his career so far). The project included Eisenstein’s footage of Mexico, a country where, like yours truly in Japan, Michael has spent much of the latter half of his life.

In Japan in the 1990s, driven by the bubble economy, there was an unprecedented rush of construction when approximately 1,000 concert halls opened during a single decade. One of these was Tokyo Pan, built by Panasonic as a multi-channel surround-sound space with hundreds of speakers imbedded in the walls and ceiling. Numerous concerts of contemporary music were held there, including a Michael Nyman concert. I had invited two Japanese musician friends to come with me to the concert, thinking it would be the Michael Nyman Band we were to see. As it turned out, it was only Michael who walked out on stage, sat at the grand piano, and proceeded to play an intense 90-minute piece harking back to his Greenaway period, with its repetitive motorik rhythms . Afterwards, I asked him, “What was that piece?” He answered, modestly: “Oh, just something I jotted down on the plane during the flight from Australia.” Would that we were all capable of such remarkable jottings!

Coming up: Michael’s erstwhile student, then producer…